For sale: one chest of drawers

(slightly used) of corpses

some drawers stick

some full of hands,

full of heads empty of thought

some chest of drawers

of chests

For sale: the buttons

once kept in that chest emptied to make room

now used by surgeons

to button your plastic together

(mint condition) action figure

posed to attract buyers

who pass hurriedly assuming

that you’re another mannequin

for sale,

more interested in the clothes

on your frame

than in your frame itself

For sale. Dolls, many varieties;

life-like screaming excreting,

IV marionette, paper

with nurse outfit,

CPR dummy, mouths agape.

For sale: used books,

used up. Words no longer function.

Cheap.

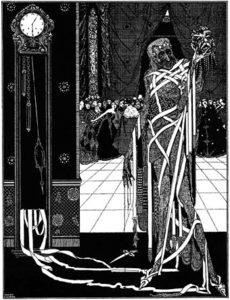

For sale: one music box

Gears in good working order (see)

as one turns over in gurney

the beeps and blips change tempo

the song box rings out its finale

with bells of mourning

For sale: bells

For sale: bells

For sale: bells

illustration is the Spice Shop by Paulo Barbieri, 1637