Uncategorized18 Jul 2021 06:15 pm

Lorraine Schein

No man is an island—

but magical women are.

Enchantresses get lonely on their islands

with only fish, gulls, and their servants for company,

and no embraces, save for the wild caresses of the sea

or what they can conjure up to pass the empty days

until some shipwrecked sailor comes their way.

On Ogygia, sea nymph Calypso

fell in love with Odysseus,

cast a singing spell on him while weaving

to ensure he’d never leave.

Odysseus stayed for seven years. Music is sorcery.

Though Calypso promised him immortality,

she finally had to let him return to sea

at the order of Zeus, and set him free.

Calypso was the first feminist Greek goddess:

she then complained to Zeus

that goddesses were not allowed

to sleep with mortals, as gods could.

But it did no good.

Sorceress Circe of Aeaea

bewitched his men with song too, then wine

that turned them all to swine.

Hermes gave Odysseus an herb called moly.

Now immune to her spell, he set them free.

Circe was in love with him also.

But it was never mutual with either enchantress—

though both were madly in love with Odysseus

getting home was his one obsession.

Magical women get lonely on their islands.

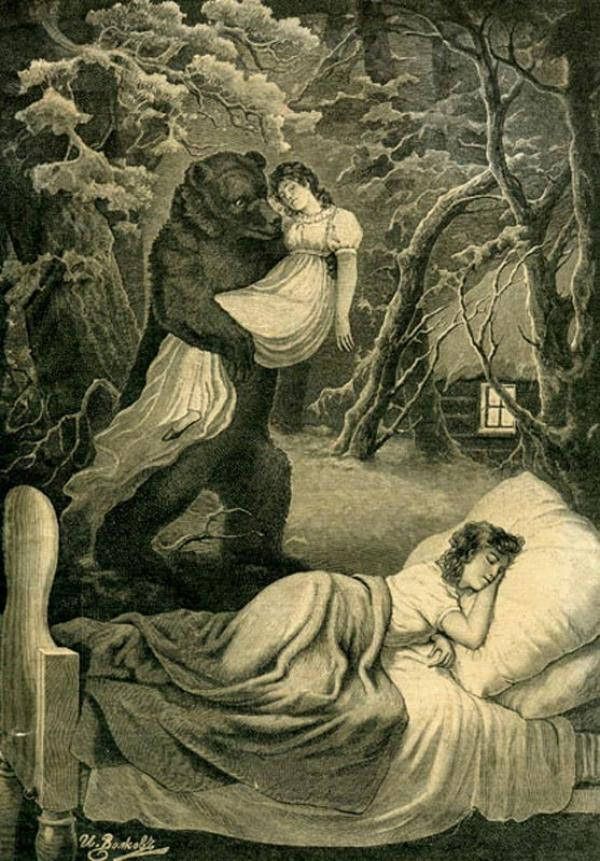

In bed, no lover whispers at their side

There’s only the murmurs of the wind and tide.

And when a sailor does arrive,

the gods tell them to set him free.

He is more important, and must continue his quest.

So obey they must,

for they are not the gods of Olympus,

or even demigods like Odysseus--

Just enchantresses, isolated on their islands,

where the men wash up like driftwood thrown ashore

or like seagulls soaring over, then seen no more.